We've been together now for forty years,

We've been together now for forty years,- An' it don't seem a day too much:

- There ain't a lady livin' in the land

- As I'd swop for my dear old Dutch.

The impoverished pair in this music-hall song are being parted - not by death, but by the workhouse. Segregation of the sexes was the rule, even for elderly married couples.

The Department for Work and Pensions now operates a reverse imposition: that a couple needs only one bedroom, despite the fact that swanky developers are increasingly building twin master bedrooms.

Today's Supreme Court hearing is looking at bedroom tax, including the needs of people with live-in carers and couples who sleep apart. I'm inevitably reminded of window tax (imposed from 1696 to 1851) and the well-known dodge of bricking up windows. There

are - possibly - some examples of this [left] in Strutton Ground, a

cobbled street near the court. Without a lot of poking around I

can't confirm that these were bricked up for tax avoidance, but the

buildings are from the right period.

There

are - possibly - some examples of this [left] in Strutton Ground, a

cobbled street near the court. Without a lot of poking around I

can't confirm that these were bricked up for tax avoidance, but the

buildings are from the right period. More disturbing are the fake bricked-up windows at Poundbury in

Dorset [right], the twentieth-century sonnet to repro - but

that's a harmless Jane Austen bonnet compared with current hideous de

luxe developments which offer potential for tax/stamp-duty avoidance.

More disturbing are the fake bricked-up windows at Poundbury in

Dorset [right], the twentieth-century sonnet to repro - but

that's a harmless Jane Austen bonnet compared with current hideous de

luxe developments which offer potential for tax/stamp-duty avoidance.

Maybe the Government could tax residential basement developments (if that's what you think of the housing stock around here, move to Bracknell) rather than count the bedrooms of people on low or no incomes.

In court I'm sitting next to the Vicar of Dibley - the real one, the Rev. Paul Nicolson, who gave permission for the TV series to be based on Turville in Buckinghamshire, his parish at the time.

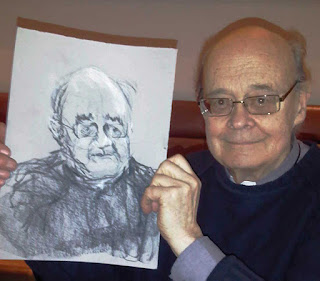

Paul Nicolson at Occupy - Paul is an indefatigable campaigner who founded the charity Z2K: its declared purpose is to fight the causes of poverty and help vulnerable debtors to gain justice against unfair systems.

I've blogged about Paul before, at the Occupy protest camp outside St Paul's cathedral, so let me dip into the archive:

He refused to pay the poll tax because he believed it was an injustice to the poorest people, but it was docked from his pay [as a vicar] anyway. 'I told the Church Commissioners they should be involved in civil disobedience like I was. I got a very short answer.'

Before becoming a vicar Paul worked in the family Champagne business. He recalls a two-week trip to Paris learning how to sell Champagne to nightclubs: 'I went to one club where there was a bottle of Veuve Clicquot on each table before you sat down. Mistinguett, the Folies Bergere star, was sitting at a table. Her legs had been insured for a million pounds because they were so beautiful. By then she was 86. A female impersonator did his impression of her while she sat holding hands with a dwarf. Then Jacques Tati walked in and sat at the bar. It was pure Toulouse Lautrec.'

I sit there drawing Paul while he fidgets, scribbles notes and (very quietly) huffs with exasperation. It's a great shame I'm not Banksy, because Paul is facing a five-figure legal bill for his latest test case, fought (and lost) on behalf of people in need.

- As always in Court 1, the portrait of the super-magistrate Sir John

Fielding, blinded at the age of 19 by eighteenth century surgical

techniques, looks down on proceedings.

There are a lot of people in the public seats, all of them very attentive. The one swigging a soft drink from a can is a solicitor. A courteous guard allows her to finish then politely takes it away.

R (on the application of MA and others) v Secretary of State for Work and Pensions; R (on the application of A) v Secretary of State for Work and Pensions; R (on the application of Rutherford and others) v Secretary of State for Work and Pensions

Category